Glory and Dishonour: Victoria Cross Heroes Whose Lives Ended in Tragedy or Disgrace by Brian Izzard

There have been so many books on Victoria Cross heroes that the London auction house Spink actually published a bibliography. Most of the books follow a similar path, focusing on the heroism. But after researching many of the stories I came to realise that there was another dimension.

As the blurb to my book points out, ‘. . . this is the first one to explore the lives of those for whom the greatest accolade did not bring contentment, happiness or lasting fame’.

In Victorian times men who upset authority were often treated harshly and Victoria Cross holders who transgressed were no exception.

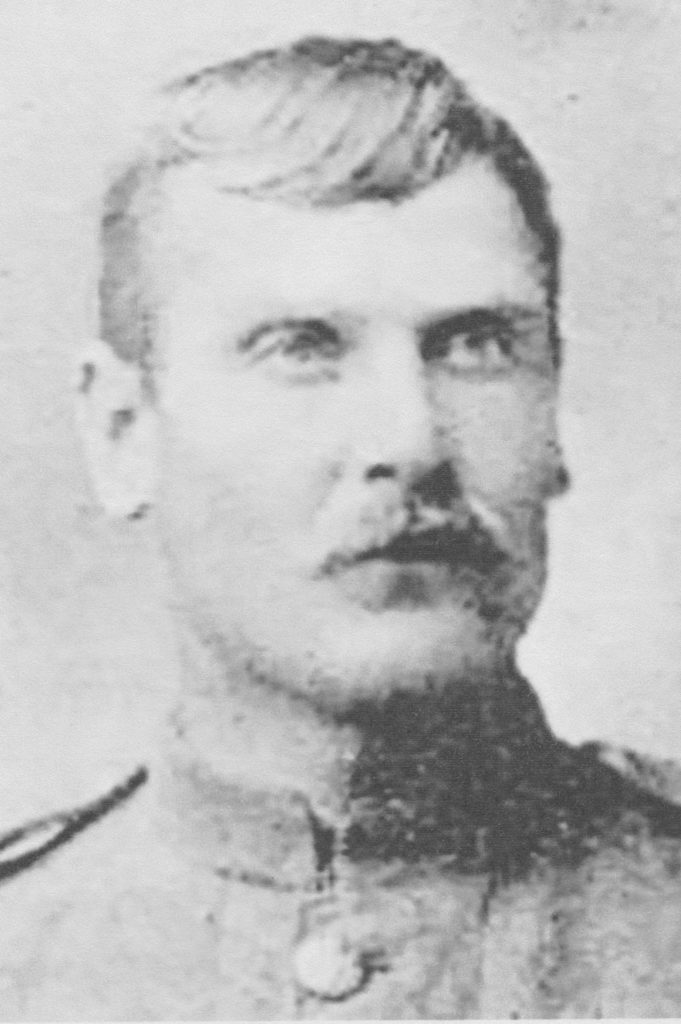

One of the saddest cases is that of George Ravenhill, who joined the Royal Scots Fusiliers at the age of 17. When the Second Boer War broke out in 1899, his battalion sailed to South Africa. In a famous action at Colenso, Ravenhill was one of the soldiers who tried to save the guns of the Royal Horse Artillery after a blunder led to them becoming trapped in a Boer ambush. Seven men, including Ravenhill, who was wounded, were awarded the VC.

After his discharge from the army he struggled to provide for his wife and three children, two sons and a daughter. They ended up in their local workhouse, Erdington, Birmingham. In 1908 Ravenhill’s plight came to the attention of Liberal MP Cecil Harmsworth, who raised the case with the Secretary of State for War, Richard Haldane [later Viscount Haldane], in the House of Commons. Haldane replied: ‘This is the first intimation we have received on this matter. The case is being investigated.’

No help came and Ravenhill, whose wife had given birth to another child, a girl, resorted to stealing some iron worth six shillings to raise money to feed his family. He was arrested and jailed.

It is to Ravenhill’s credit that despite his financial misery he had refused to pawn or sell his Victoria Cross. But if War Office bureaucracy had moved slowly to help him, especially with regard to a pension claim, it acted swiftly to dishonour him. His decoration and two campaign medals for South Africa were confiscated, and his name was removed from the Victoria Cross Register.

According to the 1911 census, Ravenhill and his wife and children were still in the workhouse. Another child had been born, but such were the family’s dire circumstances that three children were sent to Canada for fostering by wealthy families. The ex-soldier would never see them again. In 1921, aged 49, he died at his home, one room in a squalid tenement building. The hero of Colenso was buried in a plot marked only ‘36’. There were no funds for a plaque.

The unfortunate distinction of being the first army recipient to forfeit the Victoria Cross fell to James McGuire. Bizarrely, a cow led to his downfall.

For many Irishmen in the 19th century the British army offered an escape from poverty and the misery of the country's potato famine. At Enniskillen in 1849 the East India Company was recruiting for its regiments, and McGuire, then a labourer aged 21 or 22, signed on for 10 years, sailing to India to join the 1st Bengal European Fusiliers. He was awarded the Victoria Cross during the Indian Mutiny after throwing a ‘burning mass’ of ammunition boxes over a Delhi parapet and saving many lives.

After completing his service Sergeant McGuire was discharged in 1859 with a pension of one shilling a day. As the holder of the Victoria Cross he was also entitled to an annual payment of £10. McGuire returned to Ireland and at some stage went to live with an uncle, who had a small farm near Enniskillen. The ex-soldier was persuaded to loan the family £6 but the debt was never fully repaid.

McGuire, a ‘simple, quiet man and not up with the ways of the world’, took a cow belonging to his uncle as payment. He was arrested on his way to a fair, presumably to sell the animal, and a court sentenced him to nine months’ hard labour.

McGuire reportedly died a few months later. But there is speculation that he may have taken on a new identity, perhaps joining the army again, an easy thing to do in those days.

As the Victoria Cross winner Michael O’Leary observed: ‘No nation ever did bother much about its old soldiers, and why should they bother about me?’

The army veteran had been reduced to working as a doorman at a hotel near Park Lane, London, earning ‘a scant living holding umbrellas over the heads of painted actresses, crippled old ladies and richly-clad members of the plutocracy’. The hotel did not pay him a wage and he relied entirely on tips, ‘but only one person out of ten ever gives me a tip’.

In 1915 O’Leary of the Irish Guards had caught the imagination of the British public after single-handedly storming two German positions and saving many of his comrades from deadly machine-gun fire in northern France. After the war he went to Canada to start a new life but was later dogged by smuggling and bootlegging scandals.

Brian Izzard's new book Glory and Dishonour: Victoria Cross Heroes Whose Lives Ended in Tragedy or Disgrace is available for purchase now.