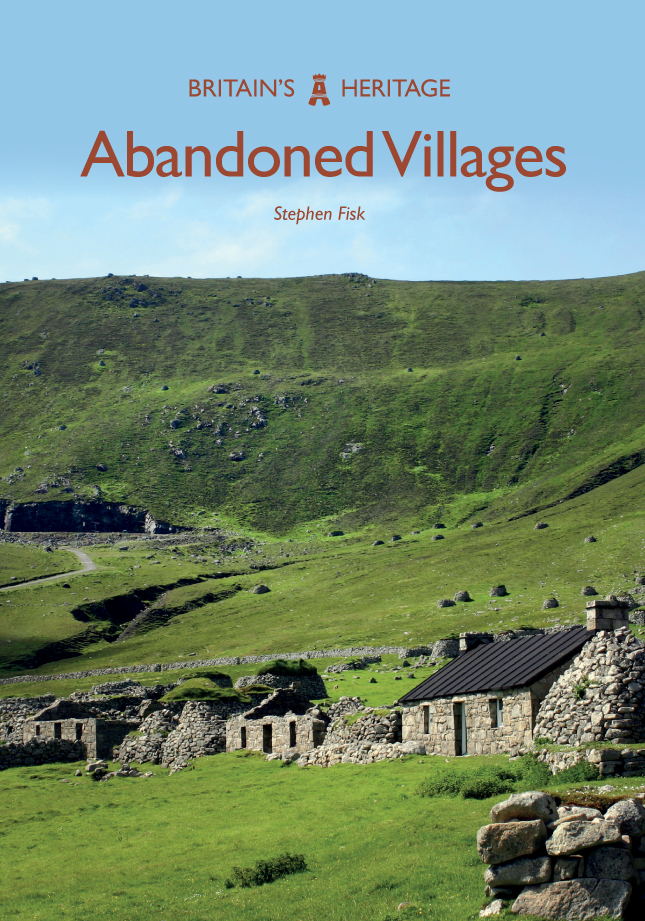

Abandoned Villages by Stephen Fisk

I retired in 2003. Having worked as a clinical psychologist I left with no plans at all for the future, but reasonably confident that new interests and activities would soon begin to come along. One of my biggest interests since then has been the abandoned villages of Britain.

An early inspiration was Richard Muir's wonderful book The Lost Villages of Britain. Before long I was exploring the sites of villages not far from my home in South Wales. Cosmeston, the only deserted medieval village that has been reconstructed; Kenfig, the castle and town built by the Anglo-Normans as part of their attempt to conquer this part of Wales, but almost completely covered by sand during huge storms in the fifteenth century.

Over the next few years I enjoyed trips to all parts of Britain. In Sussex, for example, I went to Tide Mills and Lowfield Heath. Tide Mills got its name as it was close to a flour mill driven by tidal power. The mill closed in 1883, but the village survived until the early part of World War Two. Lowfield Heath, on the main road from London to Brighton, lost its attractions after the development of Gatwick airport very close to it. By 1974 everyone had moved away and it was turned into a trading estate (but luckily one of my favourite churches was allowed to remain standing).

Another trip took me to Lancashire and Greater Manchester. Local history expert Alan Crosby was kind enough to meet me at Haslingden Grane and show me around the valley. Many fascinating ruins survive, the most splendid being Top o' th' Knoll, the home of Andrew Scholes. Andrew Scholes, otherwise known as Owd Andrey, was a poet and violinist, but remembered above all for building a cart inside his house and then finding it was just too big to get out of the door.

On the same trip I visited three reservoirs close to Rochdale. In the Cowm valley life became increasingly difficult after the reservoir was constructed and the last residents moved out in 1950. Both Watergove and Greenbooth reservoirs have textile mills and small villages submerged beneath them.

A longer and very memorable trip took me around much of Scotland. I saw several places near the sea where in various ways shifting sand led to villages being abandoned; the remains of villages close to mining and industrial enterprises that were gradually deserted after those enterprises came to an end; and in the far north of Scotland the empty sites of communities where people were evicted during the Highland Clearances of the nineteenth century.

After a while I began to think about publishing the results of my travels and research. A book or website were the options. I decided to develop a website, the Abandoned Communities website, and I am very glad I made that choice. A website makes it much easier for readers to get in touch, and I have many people to thank for telling me about abandoned villages I did not know about; people who lived in abandoned villages or their descendants who have given me information and photographs of life in their village while it still existed; and even one or two people who have explained the meaning of local words or have offered to read or interpret old documents that I was having trouble with. Having said that, I am now very grateful to Amberley for giving me a chance to produce a book as well.

Stephen Fisk's new book Abandoned Villages is available for purchase now.